- Home

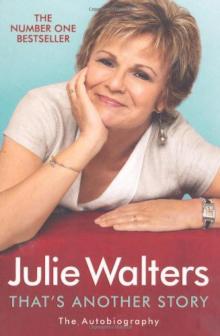

- Julie Walters

That's Another Story: The Autobiography

That's Another Story: The Autobiography Read online

Table of Contents

Title Page

Copyright Page

Dedication

Acknowledgements

Chapter 1 - ‘Five Years Ago Today’ - The Beginning

Chapter 2 - ‘This Old House’ - 69 Bishopton Road

Chapter 3 - ‘Don’t Go Out Too Far’ - Holidays

Chapter 4 - ‘A Fine Figure of a Man’ - Dad

Chapter 5 - ‘At the Third Stroke She Will Be 78’ - Grandma

Chapter 6 - ‘Mixing with Doctors’ Daughters’ - Junior School

Chapter 7 - ‘I Thought You’d Failed’ - Senior School

Chapter 8 - The Little Nurse - Work

Chapter 9 - ‘So You Want To Be an Actress?’ - Manchester

Chapter 10 - Foreign Adventure

Chapter 11 - Learning to Teach

Chapter 12 - ‘Can We Still Go on the Honeymoon?’ - Breaking Up

Chapter 13 - Life at The Everyman - Liverpool

Chapter 14 - Funny Peculiar in London

Chapter 15 - ‘We’re Missin’ Brideshead for This!’ - Victoria Wood

Chapter 16 - Ecstasy with Mike Leigh

Chapter 17 - Rita on Stage and Screen

Chapter 18 - The Two Alans

Chapter 19 - ‘I Love to Boogie’ - Oscars and BAFTAs

Chapter 20 - ‘Something There to Offend the Whole Family’ - Personal Services

Chapter 21 - The Arrival

Epilogue - Another Beginning

Film and TV

Index

Picture Credits

By the same author

Baby Talk

Maggie’s Tree

That's Another Story

JULIE WALTERS

Orion

www.orionbooks.co.uk

A Weidenfeld & Nicolson ebook

First published in Great Britain in 2008

by Weidenfeld & Nicolson

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

© Julie Walters 2008

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be

reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted,

in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical,

photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior

permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher.

The right of Julie Walters to be identified as the author

of this work has been asserted in accordance with the

Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book

is available from the British Library.

eISBN : 978 0 2978 5748 8

This ebook produced by Jouve, France

Weidenfeld & Nicolson

The Orion Publishing Group Ltd

Orion House

5 Upper Saint Martin’s Lane

London, WC2H 9EA

An Hachette Livre UK Company

www.orionbooks.co.uk

For Maisie

Acknowledgements

Firstly, my brother Tommy for introducing me to the sheer pleasure of reading and for his encouragement, enthusiasm and delight in my early ‘literary’ efforts at school. My sister-in-law, Jill Walters, for putting me right on the geography of my home town, bits of which I had long forgotten; and Professor Carl Chinn for putting her right on the bits that she’d forgotten. David Thompson for providing me with precious photographs and memories.

Paul Stevens for getting the whole thing off the ground so brilliantly and my agent Paul Lyon Maris for his tremendous support, inordinate good sense, but especially for his words of wisdom.

Alan Samson, for whom ‘thanks’ just doesn’t seem enough and without whose Albert Hall-sized knowledge of just about everything, gentle encouragement and necessary sense of humour, I would never have had the courage to write this book in the first place.

And last but by no means least, my husband Grant and my daughter Maisie for being there and listening patiently to my fears, moans and long, protracted readings of roughly written passages from this book; in short, for being who they are.

1

‘Five Years Ago Today’ - The Beginning

‘Five years ago today . . .’

It’s my mother’s voice. She is at the foot of the stairs, calling out the story of my birth, as she did on so many birthdays.

‘Ten years ago today . . .’

It is Irish, a Mayo voice worn at the edges, giving it a husky quality, which, she told me once, some men had found alluring.

‘Fifteen years ago today . . .’

Now it is soft with memory and buoyant with the telling. I was the fifth and final child to be born, each delivery producing its own particular trauma.

The first, my brother Tommy, arrived during the war in 1942. He never slept and continually scratched at his face, until eventually he was taken into hospital where his tiny hands were bandaged to prevent further harm. When Kevin, the second, was born three years later, my mother’s screams of ‘Put him back!’ apparently reached the outskirts of Birmingham. This, according to my mother and much to our amusement, was due to the inordinate size of his head. The third, a girl called Mary, was stillborn, and in order to get me to eat eggs my mother had told me that it was Mary’s refusal to do so that had caused her demise. This went on for some years until one day I challenged the assertion, pointing out that a dead baby wouldn’t have been able to speak let alone have much of an appetite. And anyway, I went on, where is she? Where is her grave? My mother went quiet. I was beginning to think she had made the whole thing up, that there never was a Mary, until my father chimed in with awful innocence, ‘Well, she was incinerated, wasn’t she? She didn’t have a proper funeral. No! That’s it! She was buried in, like, a job lot.’ That was the first time I ever saw her cry and I didn’t understand her grief, at least not for about another thirty years.

The penultimate birth was a late miscarriage, a boy, of which very little was said. Then after she was told it would be too dangerous to have any more children, I came along in 1950 on 22 February, apparently at three o’clock in the afternoon.

‘My waters broke . . .’ A slight vibrato begins. ‘Your father and I got on the bus.’ She knows I need to know and that she needs to recount it; again and again. ‘I was passing your motions.’ Well, perhaps I don’t need to know this, but I’m not sure, and no matter how many times I ask, this last detail is only ever explained by further increasingly impatient repetitions of it. Now, of course, I know and see its significance: I was shitting myself. ‘They should never have given me that big fish dinner . . .’ I am now standing in the room in St Chad’s Hospital, watching my mother, the said fish dinner having been thrown up over the pale-yellow counterpane. She is huge, about to give birth. ‘The cord was around your neck.’

‘God, Mum, I know this so well I feel as if I was actually there.’ She ignores this.

‘They got in the priest.’ I can see him, well, not really. I cast Father Sillitoe in the part, our parish priest from St Gregory’s church, round and avuncular, his red face testament to his fondness for altar wine. My brother Tommy, an altar boy himself, tells how Father Sillitoe would slip a hand under his elbow, forcing him to pour a lot more wine into the chalice than the usual mouthful. ‘They could save only one of us . . . Your father had to choose.’ My mother’s incomparable sense of drama now removes all vibrato from her voice and this last statement is made with a terrible flat resignation. Like the best of actors, she knows that less is more.

‘I chose you.’ My father chipped in on this only once that I remember. His voice is gentle and unassuming with a big, full, Birmingham, inner-city accent. He is sitting,

his hair full of plaster dust, exhausted and weathered far beyond his years, in the kitchen at 69 Bishopton Road, wet shirts dripping from the pulley above him, smelling of turps and house paint and years of cigarettes. The cigarettes weren’t just in his clothes; they were in his skin, in his sweat. He had smoked since he was ten. Even though he died in 1971, I can summon up that smell in an instant.

‘He chose you.’ Her voice is that of a sad, bewildered child. My mother’s father never chose her.

‘Yes but it doesn’t matter. It was all right in the end,’ my father soothes.

‘The priest had to give me the last rites.’

‘Yes but you were all right in the end.’

‘Extreme unction.’

‘Yeah but—Oh blimey . . .’ He knows when to give up and does so with an ironic, forgiving little laugh.

‘They took you away. I didn’t see you for a whole week.’

No one speaks.

‘Happy birthday, Julie.’

2

‘This Old House’ - 69 Bishopton Road

Number 69 Bishopton Road was a big, draughty, end-of-terrace house. There was a song around in the fifties called ‘This Old House’, with lyrics like, ‘Ain’t got time to fix the windows, ain’t got time to fix the floors.’ Whenever it was played on the radio my mother sang along with such gusto and empathy that as a small child, whose universe began and ended at our back gate, I presumed that it was being sung specifically about our house.

Similarly once, whilst I was watching Watch with Mother on my own, aged about three, a kindly lady sat there holding a teddy bear and waving its paw straight at the camera, saying, ‘Look, Teddy, there is a little girl watching us and she’s got a teddy just like you!’ I was off that sofa and into the kitchen before you could say Andy Pandy, screaming at my mother that the lady on television could not only see me but she had spoken to me and she knew about Teddy as well, and there might be a damp patch on the sofa; but that was Teddy, not me. My mother simply replied mysteriously, ‘Don’t listen to Grandma.’ It was only when I asked my father why, when there were Tom cats, were there not any Kev cats, and he explained that Tom cats were not named after my older brother, that it began to dawn on me that the sun didn’t shine out of my arse.

At the far end of Smethwick’s Bishopton Road, about two hundred yards down, was Lightwoods Park, right on the border of Bearwood, which is part of the Black Country around Birmingham. As a child I was forbidden to go to the park unaccompanied because of ‘strange men’, the park keeper himself being quite possibly one of the strangest. Lightwoods Park, which covered about ten acres, had a bandstand with a large, domed roof, kept aloft by several spindly-looking, wrought-iron pillars, whose top-heavy nature sent my brother Tommy into a panic when he was small, with tearful claims that it was ‘Too big up there’. There were a set of swings, a couple of roundabouts, a see-saw and a defunct witch’s hat. This last was a conical roundabout in the shape of a witch’s hat, the top of which was balanced on top of a tall pole and, because of this shape, it not only went round but veered crazily up and down as well as from side to side. Next to this play area was the pond, about an acre of water, upon which people sailed their model boats and suchlike, whilst in hot weather it became a muddy soup of children and dogs, paddling and swimming. At the edge of the park stood (and still stands) Lightwoods House, built in 1791 for Jonathan Grundy, a Leicestershire maltster. It was eventually donated to Birmingham City Council in a philanthropic act by Alexander Macomb Chance, one of the Chance glass-making family of Spon Lane, Smethwick. In my day it had been downgraded to a caf’ where teas, ices and suchlike could be bought.

Never were my mother’s warnings to keep out of the park fiercer than during the summer holidays when the annual funfair came for a week. I found the smell of hot dogs, diesel and candyfloss, the garish colours, the loud pop music, half drowned out by the noise of generators, totally alluring, and I loved rides like the dodgems and the bumping cars where swarthy, muscle-bound young men, in dirty jeans and covered in tattoos, would take your money and jump on the back of your car, or better still on the waltzers, where the more you screamed the faster they would whip your car around. The fairground was always full of groups of adolescent girls careering drunkenly about in a whirl of light-headed hysteria and something closely akin to post-coital relief. According to my mother, ‘The fair attracted the wrong sort and no decent girl would be interested in boys like these; they were low types from God knows where,’ and were to be kept away from. Needless to say I went every year, mostly avoiding being found out. The fairground boys - the waltzer boy in particular, so poignantly described in Victoria Wood’s song ‘I Want to be Fourteen Again’, ‘The coloured lights reflected in the Brylcreem in his hair’ - played leading roles in an early fantasy of mine about living in a caravan, working on a stall involving goldfish and smelling of petrol.

Our end of the street formed the junction with Long Hyde Road. Only about a hundred metres long, it was short and there were rarely more than two or three cars parked in it at a time, one of them being my father’s, when it was not parked in the garage at the back. Dad always owned a car except for when he first started his business, when he pushed around from job to job a wooden handcart laden with ladders and tools. On the side it had THOS. WALTERS Ltd, builders and decorators and the address, painted by a signwriter. This, however, was before I was born. The first car I remember was in fact a small, bright-yellow van, which my father referred to as Sally.

Sally had no side windows at the back, just two little square ones, one in each of the back doors, and so her rear end consisted of a fairly dark space that was always full of tools, paint, bits of wood and the odd paint-spattered rag: the general requisites and detritus of my father’s work life. Yet if we went out in Sally as a family, she would be transformed; Dad would shift everything out of the back and sling in an old bus seat for my brothers and me to sit on. I can see it now and not only see it but feel it. It had a silky, soft pile if you ran your hand one way across it, although this became quite uncomfortably rough and prickly if you had the misfortune to run it the other way. It had an abstract, jazzy, brown and green pattern against a dull, beige background and the whole thing was edged in creased brown leather. This bit of ‘necessity being the mother of invention’ thinking on my father’s part worked really well unless we had to stop suddenly for any reason, such as at a traffic light or a pelican crossing or when arriving home again. The seat, having no support at the back of it, would abruptly tip over backwards, sending all of us sprawling into a chaotic backward roll. So any journey would mainly be spent scrambling about in the semi-darkness, getting the seat upright again just in time for the three of us with a mighty, united scream of ‘Daaaaaaaad!’ to be sent flying once more. In fact every journey ended like this as we pulled up outside the house, accompanied by my grandmother’s declaration, if she was with us, of ‘We’ve landed!’

Sally was eventually replaced by a far superior and very ‘modern’ Ford Esquire estate. It was a sedate grey colour and its main advantage was that the estate bit at the back served as extra passenger space for small persons when the car was at capacity. Of course this was long before seatbelt laws and would be illegal today. The small person was inevitably me and it meant that not only could I travel staring out of the back window at the car behind, possibly making faces or breathing on the glass and writing fascinating back-to-front messages, like ‘ylimaf neila na yb detcudba gnieb ma I !!pleH’ for the driver behind to ignore, but I could also avoid being poked or teased by my brothers.

The other advantage of this new acquisition was that it soon became clear that Dermot Boyle, the boy who lived opposite, with whom I played on a regular basis, was envious. As may be obvious from the name, the Boyles were an Irish family. Mr Boyle was a builder’s labourer who came from Kerry and, as my dad would say, liked a drink. He had very red, permanently wet lips that appeared to work independently of the rest of his face and, indeed, independently of any

thing that he might happen to be saying. They flopped around clumsily, an impediment to the words that came pouring through them in unintelligible strings. These were buoyed up on clouds of alcoholic breath and always accompanied by blizzards of spit. The whole thing was pretty hard to avoid for, once buttonholed, Mr Boyle would always address a person no more than three inches from their face, due to his poor eyesight. He was severely short-sighted, which meant he was forced to wear glasses with lenses so thick that it was like looking down a couple of telescopes the wrong way, his eyes becoming tiny, blue, distant dots. We often stood giggling at the upstairs window, behind the nets, watching Pat Boyle wobble up the street on his pushbike and stand swaying for a good ten minutes, trying to get his key in the front door lock, his face jammed right up against it. Then, eventually, the door would be opened by the long-suffering Mrs Boyle and Pat, with key still in hand poised to slip it into the lock, would go lurching forward like a pantomime drunk, Mrs B berating him as he stumbled in. The irony of the whole Boyle saga was that Mrs Boyle, who never took a drink in her life, died of liver cancer and Mr Boyle, who was rarely sober as far as I know, died of natural causes.

I am ashamed to say that I exploited Dermot’s envy of our car to the maximum and with relish. If he happened to be out playing on the street by himself, and the car was appropriately parked, I would sit provocatively on the front bumper, caressing its shiny chrome with one hand, the other stretched backwards across the bonnet, occasionally fingering the Ford insignia, one leg crossed over the other, swinging my foot nonchalantly back and forth, chatting inanely on whilst secretly clocking Dermot’s reaction. He would sit on the kerb by the side of the road, usually eating a piece of his mother’s home-made cake, squirming and covering his eyes. At last he would run off, mid-conversation, down the entry that led round to the back of his house, shouting ‘Stop it!’ and spraying cake crumbs, as he went.

That's Another Story: The Autobiography

That's Another Story: The Autobiography