- Home

- Julie Walters

That's Another Story: The Autobiography Page 15

That's Another Story: The Autobiography Read online

Page 15

Amongst the workforce were a number of mentally handicapped people and one such girl worked on the same floor as me. She was blonde, sweet, innocent and slow, obviously much younger than her actual years, always happy, smiling and willing, and rather pretty. Every day of her life while I was there, she was subjected to humiliating teasing at the hands of a group of four or five men. This usually took the form of lewd sexual jibes, which for the most part seemed to go over her head, but sometimes I saw her emerge from behind a partition adjusting her clothing, with raucous laughter coming from the men on the other side. At first I felt impotent, because of my status as a temp, but I became very upset on behalf of this vulnerable girl, obsessing about the awful, bullying behaviour to the point where I couldn’t concentrate on my ‘screwing’ and I began to lose sleep at night. In the end I took it upon myself to approach the foreman and told him what I had witnessed.

‘No, it’s only a bit of fun. She loves it. She’s been working here years. No, no, don’t worry your pretty little head!’

I don’t know how I stopped my hand from forming a fist and punching his big pockmarked nose right into his ugly, pockmarked face.

‘No,’ I said, ‘I want you to worry yours.’

When I checked in with Manpower on the Friday of that week, they said that I would be going somewhere else to work on the Monday. It seems the factory no longer needed my services.

Whilst in a practical sense I missed the comforts of home and the institutional nature of life in the nurses’ home - where the domestic side of everyday living, like laundry, cleaning and cooking, were completely taken care of - I found my new life of cohabitation both challenging and exciting. There in the tiny kitchen at Maple Avenue, from a fairly narrow culinary repertoire, DT gave me my first real cookery lessons. How to boil potatoes and how to make spaghetti bolognese, two ‘skills’ that have formed the basis of the cook I am today!

It was here that the exploding haggis incident occurred. I had just left the kitchen for a second when a bang like a football rupturing brought me running back in to find the innards of a haggis, which had been boiling on the stove, dripping from the ceiling, the thing having burst in the pan. The downstairs neighbour stood on the landing looking a touch scared. This was after the pubic hair business and, unsure whether this neighbour was the anonymous author of the note, I was struck dumb, so the two of us just stood there, him wondering what on earth had happened and me picturing him gingerly picking my pubes out of the bath.

Another disaster took place when I decided to surprise DT with something a little different and purchased for the hefty sum of six-pence a pig’s head. I popped it in the Baby Belling oven with a few rashers of streaky bacon artistically placed on top of the head, two between the ears and a couple down each side, which had the effect of making it look like hair and, without realising it, a prototype for Miss Piggy. I couldn’t wait for DT to arrive home from college; the smell from the kitchen was mouth-watering. However, when he finally did get home and the time came to reveal my culinary surprise, I opened the oven door only to find a sight worthy of a Hammer horror film. The head had indeed roasted to a gorgeous golden brown and the rashers had crisped into a set of curls, but out through the eyes, nose and mouth was oozing the creature’s brain, which I didn’t even know was in there, and it was a sludgy, burnt, greyish colour. We had fish and chips that night.

One Saturday, having gained a little confidence, I invited a couple of friends around for lunch. The lunch was to consist of a quiche, a fairly unusual dish in those days and very trendy, plus some salad, followed by apple crumble and custard. I was totally thrilled with the result as I got the two dishes out of the oven. They looked cookery-book perfect, golden and delicious, but when we came to eat the quiche, no one could get their knife through the pastry. What made it worse is that no one said a word; they just soldiered silently on, trying to force their knives to cut into it, one friend placing his knifetip down vertically and banging on the end of the handle with the palm of his hand, hammer-and-chisel style.

‘Look, look, since we haven’t got a pneumatic drill, it might be best to just scrape the filling out and eat that, and if anyone’s got a roof that needs mending please feel free to take the - what I laughingly call - pastry case home with you.’

I have never made pastry since. I’ve always seen cooking as some sort of measure of my womanhood, a kind of performance that I must rise to, and so apart from preparing meals for my own family, it has been an unspeakable trial. The thought of giving a dinner party to people I don’t really know is anathema to me. Only in the last few years have I been able to enjoy cooking to a degree and see it for what it actually is, and for that I thank Queen Delia.

In January 1970, I had my audition for a place at Manchester Polytechnic School of Theatre. I had bought a couple of books of audition speeches as I had been asked to prepare three pieces, one of which had to be Shakespeare. I chose Lady Macbeth, Macbeth being the only Shakespeare I knew, having studied it at O level. The other two I barely remember, except that one was from a play I had never heard of, with a speech by a character contemplating suicide, and the other was a play by Clemence Dane, whom I had also never heard of. I was interviewed on the day by Edward Argent, the principal of the school, who was wearing a black velvet jacket. I recall thinking that this was a good sign as I was wearing my new black velvet trouser suit with the bell bottoms, the tunic-style top being cinched in at the waist by a thin, black-leather belt belonging to DT, and my new knee-length, black leather boots.

‘So you want to be an actress?’ He was a round, teddy-bearish man, with dark, twinkling eyes, thick dark hair and a full beard, threaded through with grey.

‘No. I am an actress,’ I said. ‘Whether I am employed as such is another matter, but that’s what I am; I am an actress.’ I believed that absolutely and felt that if he were to turn me down, it would be his loss.

‘So, do you think you’ll be able to learn anything here then?’

‘Oh yes, I’ll be learning about the actress that I am and how to use what I have.’

He then asked me to stand up and perform my pieces. Never since have I performed anything, first time, with such confidence. First of all I did my Lady M, the ‘screw your courage to the sticking place’ speech, feeling totally in tune with every single line. I was pleased with it, sensing that I had made the right impression, and then, buoyed up by this, I went on to my second piece, the suicide speech. Again I soared through it, convinced that I was completely at one with the character, that I was inside her skin.

Edward Argent didn’t say anything straight away, just creaked slightly in his chair. ‘Mmm, that was interesting and very, very good.’ I felt as if I might just float up into the air buoyed up by my very own ego, but then, ‘Tell me, why did you choose to play a man’s part?’

‘Oh . . .’ I laughed; what the hell was he talking about? A man’s part? My brain instantly melted into a fuzz of anxiety. And then I realised that because I’d bought a book of audition speeches, I didn’t really know the plays that the speeches were taken from and therefore, of course, I didn’t really know the characters either. Clearly there was more to this than my just acting words off the page, regardless of context.

I laughed again. ‘Oh, I just thought it would be . . . you know . . . I thought . . . Oh . . . Oh . . . Oh, what the hell, I had no idea it was a man, I just liked it and I wanted to play that speech and express those feelings.’

Now he laughed.

‘I like your honesty, good for you. Now what else have you got for me?’

‘I bet you can’t wait!’ I laughed nervously. ‘It’s by Clemence Dane and before you ask, no, I don’t know anything about him and I haven’t read the play either, but I think he must be pretty good, judging from this speech anyway.’

‘Oh yes . . . Incidentally, Clemence Dane is a woman. Fire away!’

About three weeks later, I received a letter accepting me on the course, to start the following Sept

ember, but this depended on my gaining one more GCE, as five were required in those days in order to teach. I instantly embarked on a course one evening a week at a college in Stockport, to study GCE Anatomy and Physiology. This was about as useful to my future as an actress as a lawnmower would have been, but as it was now February, and having missed the first term and almost half of the second term, with the exams coming up in June, I thought it best to choose a subject that I already had some knowledge of. Because of my nursing course, this seemed to be the best choice and, indeed, I managed to pass it with a grade two, my best grade to date.

In the summer of 1970, DT and I decided to hitch-hike down to Arcachon on the south-west coast of France, camping as we went. He had borrowed an old tent belonging to his father. The tent was stowed in an ancient, stained, green-canvas tote bag and had been in there since it was last used, some twenty-odd years before, probably for his father’s National Service. Our first stop, after finding it very difficult to secure lifts in France, was at a campsite in the Bois de Boulogne on the outskirts of Paris. We arrived in the evening, just as people were preparing their evening meals. I looked around at the state-of-the-art tents (the French take camping and caravanning very seriously), and theirs were all, without exception, brightly coloured, modern jobs, blue, green, red and yellow, with bendy poles that screwed together. Some had separate bedrooms and covered extensions to sit out under. People were cooking elaborate meals on full gas ranges, while others were barbecuing or drinking wine at elegantly laid-out tables, complete with vivid tablecloths and proper cutlery. There was that smell of coffee and garlic wafting in the air, which made me excited about setting up camp and cooking our very first meal out in the open. Then DT got the tent out.

It wouldn’t come out at first and required me to hold on to the bottom of the bag while DT tugged it free. When he finally did so, it came out so suddenly that he went careering backwards and fell on his arse on top of a child’s beach ball, causing it to burst with quite a bang and the child, almost simultaneously, burst into tears. I went immediately to the rescue with my school French, which up until this point I had been fairly proud of.

‘Oh, je me remercie! Pardonnez nous! Nous acheterons un bal nouveau.’

I noticed the man opposite, who had hitherto been engrossed in his barbecue, begin to titter and mutter something into the tent. This brought his wife out, who stood and joined in, both openly staring and enjoying the scene. Then the child’s father came over, and I was off again.

‘Oh, je me remercie! Mon ami est un imb’cile! Pardonnez nous, s’il vous plaıt!’

‘Oh, it’s all right, love, he’s got another one. We thought you were the local theatre group, come to put on a bit of slapstick for us!’ And he laughed a big, fat-bellied, Barnsley laugh. Scooping up the bawling child, he made to leave, but as he passed the spilt contents of the tote bag, he dropped down on to his haunches and, turning over the wooden tent pegs and picking up the not insubstantial wooden mallet that was needed to knock them into the ground, he said, ‘Good God ! Where did you get this from? The Imperial War Museum?’ Another big-bellied laugh. ‘Eh, Maureen, come over here and have a look at this! Jesus! It’s like Camping Through the Ages. When was this last used? The Crimea?’

Secretly I was a bit miffed, but putting a brave face on it I joined in with the good humour, and DT and I started to erect the cause of the hilarity. It was made from extremely thick and heavy green canvas and, as we unfolded it, we noticed several mysterious brown stains and a couple of small holes, just to add to its allure, whilst every crease and fold was full of long-dead flies, spiders and cobwebs.

‘Oh! Brought your insect collection with you, have you?’

More laughter, and by now we had attracted a small audience. Putting the tent up then became an activity for the entire camp. The man opposite brought over his mallet and was knocking in the wooden tent pegs, while the Barnsley couple were trying to lay flat the filthy and extremely thin groundsheet, while laughing and marvelling at the age of the thing; it was not sewn in like today’s models, but simply attached to the main tent by a series of toggles and hooks. Finally it was up. We got out our primus stove and I heated up some frankfurters and beans, but every so often a little group would gather and watch us as if we were an exhibit. Going to fetch water in the green canvas bucket with the white rope handle had people fairly rushing from their tents to point and ‘ooh’ and laugh.

We had done well on the first leg of our journey to Dover, securing lifts easily, but when we got to Calais we waited hours for a lift that took us no distance at all, and had to wait some time again until a kindly French lorry driver stopped and took us all the way to Paris. He suggested that DT’s very long hair might be the cause of people’s reluctance to pick us up and if it was cut short we might have more luck. So it was a pretty clean-cut DT who stood on the roadside thumbing a lift to Poitiers the next day and there was a rubbish bin full of red curls on the edge of the Bois de Boulogne.

It was an idyllic holiday. Camping in amongst the cypress trees in the sand-blown site at Arcachon, the hot sun bringing out their clean, astringent scent, and sitting at the pavement cafe’s, sipping huge cups of milky coffee while we observed the passing folk, giving them histories and characters and relationships, passing judgement and laughing is set like crystal in my mind. Even taking into account the antiquated tent and the difficulty with rides - not to mention the Spanish lorry driver who offered us a lift from Arcachon to Calais on the way home and proceeded to molest me as I sat on the engine in the middle, between him and DT, something I tolerated in silence because the lift was so valuable but which I avenged with a quick, sharp knee to the balls in the car park at the ferry terminal while DT was in the lavatory - it set a joyous benchmark for every holiday that has followed since.

From the moment I started at Manchester Polytechnic School of Theatre, I felt as if I belonged. It was as if I had been struggling uphill in the wrong gear all my life. Now, everything made sense, everything connected and fitted together. However, I did have a little trouble staying awake in the History of Theatre classes, and I tended to dread and try to get out of the make-up classes, which I found a trial because I might have to remove the thick layers of mascara and black kohl eye make-up that I daubed on every morning after removing the previous day’s lot. This was always done in the privacy of the locked bathroom or, in the post-pubic days of Maple Avenue, in the kitchen, with DT under strict instructions to keep out. I hadn’t allowed a single person, except possibly my parents, and then very briefly, to see me devoid of eye make-up for about three years: in fact, from the moment I first started to wear it, when I realised the effect it had on my eyes, making them darker and larger. Without it I thought myself ugly in the extreme. I had, and of course have, tiny eyes; nowadays this rarely crosses my mind but back then we had just come out of the sixties and eyes simply had to be huge. Girls wanted to look like Twiggy, waiflike, flat-chested, stick-limbed, eyes wide with innocence, or more likely starvation, as not many young women had Twiggy’s natural skinniness. So my eye make-up started at my browbone and very nearly finished at my cheek, much in the style of Fenella Fielding, except without the wig. Every time we had a class I would suffer acute embarrassment if I just had to remove a little; I never removed the mascara and I only ever partially removed the kohl. One Sunday morning, in my second year, I was luxuriating in the bath, having washed my face free of probably several days’ worth of eye make-up, when the boyfriend of the girl from upstairs and his mates, having heard from DT that I was having a bath, started banging on the door and demanding to see what I looked like without my make-up.

‘Come on, let’s see you without your war paint!’

I can remember feeling quite sick at the thought of them witnessing the exposing ugliness of my bare face. I lay silently in the bath without moving a muscle, a flannel over my eyes, until they went away, long after the water had gone cold, and I blushed whenever I bumped into them afterwards.

&nbs

p; This belief that I became acceptable and attractive to others only when I had emphasised my eyes with a black pencil line went on, but in a less and less extreme way as the years went by, until my thirties and it only stopped completely when I met my husband. It was largely cured, though, by having to be made up for filming. When I first started out, I would go into the make-up bus with a tiny line around my eyes and a very light scraping of mascara, thinking that the make-up artist would never notice, only to have it wiped off almost instantly and dismissed as a bit of ‘slap’ left on from the night before. So, of course, I would try a little less and then a little less still, until it just wasn’t worth it any more, and what a relief it was to finally accept the way I looked.

There are so many legendary tales about famous actors presenting themselves to be made up when already in full slap and I didn’t want to belong to this absurdly deluded band. There was one such story going the rounds about a famous opera singer who was playing a character who wore a wig and, during the course of the story, the wig was to be ripped off to comically reveal that he was really bald. The singer himself was actually bald and wore a full wig at all times to conceal the fact. It was such a sensitive issue that the wig maker for the opera was instructed never to allude to the fact that this man was wearing a wig and to treat him as if it was indeed his real hair. This meant that instead of using his own natural baldness, a bald cap had to be made to fit over his own personal wig and another wig, the one to be ripped off in the course of the action, had to be made to fit over that.

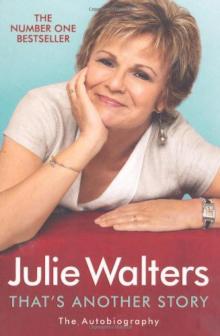

That's Another Story: The Autobiography

That's Another Story: The Autobiography